I made a decision recently to extricate myself from a couple projects that I took on while I was on an upswing, and no longer have the energy to be a part of. When I did this, I knew I was doing what was necessary given my recent struggles. Still, I’ve been ruminating over the decision, flogging myself for having not lived up to some external ideal of productivity, and for having let people down in some way with my departures. Depression feeds off rumination, especially rumination over the manifold ways in which I am not free—and by indulging this rumination, I realized I am allowing myself to get uncomfortably close to the abyss. I decided that I needed to shift my focus away from society and consider my role as personal master, jailer, and oppressor.

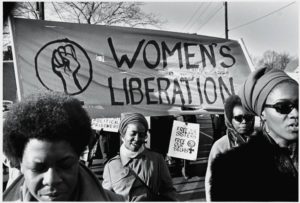

This is not to say that I’m now dismissing the ways in which society binds me; rather, I want to embrace the ways in which I can free myself. I want to live as freely as possible, within the scope of my current ability, and I want to reject ideas that stifle freedom. I can’t ask more of the Universe than I’m willing to do. If I can’t cultivate freedom within myself, how can I help birth it into the world?

This is a proclamation of my intention to work towards self-emancipation. These statements counter messages I am told by society; messages I have internalized and let take residence in my psyche, that now manifest as insecurities. Now I bring those messages into the light, refute them, and start the slow process of rooting out my subconscious acceptance of them. In this process I’m speaking mainly to myself, but I also want to reach out to anyone else who might need a nudge towards freedom in one of these areas.

I am free to be wrong

Even if I should know the answer, sometimes I don’t. That’s fine. It’s fine to forget in the moment, to remember five minutes later, to never remember. It’s fine to have never known. Only by being wrong can I test the limits of my knowledge and expand them. It’s also fine to be wrong in my actions or speech towards someone else or towards myself, as long as I recognize my wrongness and make amends. Just avoid being loud and wrong if at all possible. No one is free to be loud and wrong.

Our/my fear of being wrong is probably ableist, anyway. Subconsciously I’m probably recoiling from looking foolish, or feeble, or intellectually weak. Freedom is a place where being wrong—but being honest about it and open to learning within your capabilities—is encouraged.

I am free to fuck up

Of course I’m going to try not to make mistakes, but I will. If I didn’t, that would mean I was habitually doing things I had done way too many times before. I am human. I make mistakes. I just try to learn from them. Sometimes I don’t, and that’s valid too. I enact and embody my freedom by rejecting our individualistic, achievement-obsessed culture’s devaluation of “stupid questions”, mistakes, and failure.

I am free to take too long

This is more on nonlinear time; I’m also thinking about nonlinear/nontraditional life trajectories and “nontraditional” brains here. I might take too long to get out of the house because I was crazy in the morning and so I’m late to school. I might take too long to get through school because I was crazy for a decade and so I’m late to graduation.

I am free to say no

By saying no to opportunities I feel lukewarm about, I dodge roadblocks that might impede my ability to make room within time to accomplish things I feel passionate about. By saying no to participating in actions I’d rather not, I reinforce my boundaries and solidify my sense of purpose. Too many of us do not have the ability to say “no” in manifold arenas of our lives. Where we can, we must. “No” is a freedom word. The word “no”, when propelled from the mouth at a right angle, vibrates at the exact same frequency as Harriet Tubman’s soul. Or so I’ve heard.

I am free to change my mind

Yes, I said “yes.” But I’m saying “no” now. Absent guilt. This, too, is an embodiment of freedom.

I am free to define my own values, and I am free to reject values that aren’t mine

I no longer have to play enforcer of societal standards and values. I can keep the values I agree with, discard those I don’t, and adopt a multitude that aren’t important to the society I live in. Because it’s in the interest of white supremacy and capitalism and patriarchy that I flog myself—

for not living up to an ideal of financial stability and respectability,

not being hyper-productive,

not being ashamed of my fatness, my queerness, my craziness, and my blackness,

not being willing to work twice as hard to get half as much,

not being willing to perpetually starve myself to obtain a socially acceptable body,

not being willing to humble my desire for a collectivist world at the feet of my need for long-term security,

not being willing to transfer the pain of seeing the world as it is into a misguided defense of the status quo

—and that is precisely why I can’t engage in it. Values derived from a white supremacist imperialist capitalist patriarchy have traceable ties to my bondage, past present and future.

I am free to think of myself first as long as that doesn’t result in irreparable harm to someone else

Discomfort is going to occur for other people when I insist on firm boundaries or when I reclaim my energy and time. Discomfort is not irreparable harm, though. I have to recognize that although it is uncomfortable for both myself and whoever is on the other end of my self-protective act, ultimately I have to power through our discomfort and take the action that is best for me in the moment. No one is served by a miserable martyr.

I am free to survive thrive by whatever means are available to me in the current system

I want to live my best life, by any means necessary, and avoid hurting others in the process (at least as much as is possible in this world). Since I’ve rejected cultural values that aren’t mine, that also means I’ve rejected cultural values about what I am allowed to have access to as an oppressed person and how I’m expected to obtain material items. Corporations are now people, right?—and corporations are allowed to be financially irresponsible with no moral penalty. So I’m appropriating the right to financial amorality corporations enjoy.

I am free to make art that is shit

Without stabbing myself in the gut every time I look at it. Without wishing I had never made it. If I don’t make shit I’ll never make anything worthwhile, because I won’t know worthwhile from shit.

I am free to do something that someone else has already done as long as what I make is mine

Derivativity has to be authorized. My fear of retreading ground has killed so much inspiration. I know I have already written about things hundreds of people have written about, yet I use potential derivativity as an excuse to shoot down ideas. I should allow ideas to live their lives, give them shape, and see how they evolve. I can’t judge their originality until after they have matured. And even if I did make something completely derivative, that doesn’t discount its worth as an expression of creativity, only as an embodiment of originality. In my view, as long as what I create has honestly been synthesized in my own head, then it is creative, it is art. It might not be good, but I’m already free on that axis.

I am free to meander through life and not have a clear plan at all times

“Meander” isn’t necessarily a good way to describe why my life trajectory is skewed, but I feel like it’s describing my behavior recently. I made a shift in my plans for after I finish at UCLA, and I’ve been shaming myself for it occasionally, even though I know it’s in my best interest. The shift is further away from a guaranteed source of high income, and so I find myself reinforcing capitalist ideas about my self-worth being tied to my ability to generate profit for someone else (and in turn, generate some level of financial security for myself). Carving out a way to follow my passion is necessary for me to continue to exist in this world on any meaningful level—this I know. And I know the guilt I feel for taking so long to find my path is not intrinsic to me. It has wormed its way into my subconscious, but it isn’t my own.

I am free to be a “late bloomer”

Our culture, my culture at least, is obsessed with early achievement. We laud child prodigies and the “30 under 30” types. This has to be connected in some way with our culture’s inability to think long-term, our attitude towards our survival that sees burning out as preferable to fading away—or to constraining our consumption so that neither occurs. Briefly, I had a glimpse of prodigiousness as a child, and then it was gone, and it was just darkness for years. I’m coming back into the light, wary of its power but eager to take in its warmth. I cannot allow the sweetness of this moment to be soured by social expectations of age-appropriate achievement that aren’t even based in reality.

In these small ways

I am making space for abundance in my life,

I am cultivating a dialogue with my demons

that acknowledges my role in nursing them,

and I am instantiating freedom in small plots

where otherwise it did not grow.

I have these competing demands for my “free time” at home, and it generates anxiety because I feel like I can’t get everything done, like there’s not enough time.

I have these competing demands for my “free time” at home, and it generates anxiety because I feel like I can’t get everything done, like there’s not enough time.